Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny — English National Opera, London Coliseum

The ticket price is, as the opera itself might argue, the least of what you'll pay — but it is very much worth it.

The ENO's season has been admirably broad, but nothing else in the programme bites quite like this, a brief, three-night staging of Weill and Brecht's Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny. Two performances remain, on the 18th and 20th. Act accordingly.

An epic three-part opera brimming with sharp satire and unforgettable music, Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny explores the fragility of a society obsessed with wealth and pleasure. When three fugitives from justice find themselves in the City of Mahagonny, in the north of the USA, they decide to set up a hedonistic playground for those who crave indulgence. Among the visitors are Jenny, one of several sex workers, and Jimmy, one of four Alaskan lumberjacks, whose fates intertwine with Mahagonny’s rise and inevitable collapse.

This is opera with its corset unlaced. Written nearly a century ago, it carries expletives, frank sexuality and violence without apology. Weill collides classical orchestral tradition with the louche sounds of 1920s America, while Brecht's libretto, rendered into English with real swagger by Jeremy Sams, makes the whole thing feel less like culture and more like an indictment. In 2026, that indictment lands freshly: wealth buys acquittal, poverty earns execution, and a society built entirely on transaction destroys what is most human. Brecht was writing satire. Jamie Manton's production suggests we've been living it.

Read the synopsis here

Milla Clarke's design strips the stage to its skeleton, we can see the workings as this city is built, we know it's theatrical with rigs exposed, wings visible, a white box that begins as a criminal's lorry before receiving a splash of red paint and rotating on castors to reveal Mahagonny's interior life in squalid glimpses. Treadmills carry the new arrivals forward as they sing of desire Lizzi Gee’s choreography is sharp and subtle. The chorus floods in from the stalls clutching phones, streaming content, seeing only themselves. Director Jamie Manton has absorbed his Brecht and diluted it just enough to keep the evening moving, the alienation effects are present but worn lightly. A megaphone here, a conspicuously labelled sign there (WC. Mahagonny. Sex. Eat.) The hurricane threatening to destroy the city arrives onstage in tights and tap shoes, irreverent. It is one of the production's glorious smirks, and it earns it. Camp as menalovent threat, talent as tempest, the chorus waving in and out with the dancers advances, it brought out giggles. My companion was delighted.

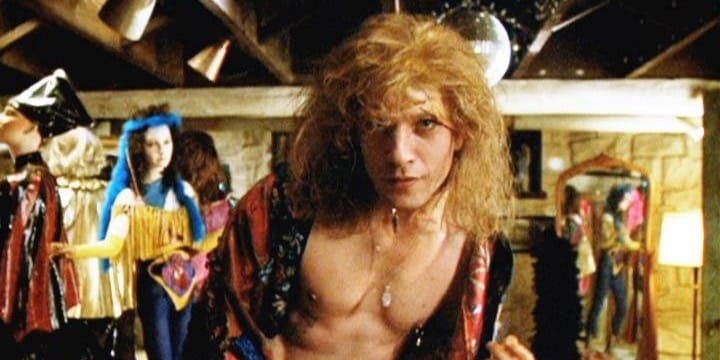

Where this revival distinguishes itself is in refusing to sanitise the opera's sexuality. Jenny's companions include two rent boys, dancers Damon Gould and Adam Taylor , presented not as provocation but as fact, people with agency and somewhere to be. It shifts the moral weight meaningfully, in this opera asking who gets to be human under capitalism, the queer lens crystallises. Brecht, one feels, would have approved.

Rosie Aldridge as Begbick is a towering, commanding presence, her mezzo equally capable of cracking like a whip or unfurling into something unexpectedly tender. Simon O'Neill as Jimmy is the evening's beating heart, his voice warm, fluid, and devastating in the final act when Jimmy is condemned not for violence but for an unpaid debt, while a murderer walks free having paid his way out. Danielle de Niese as Jenny brings easy charisma to the Alabama Song ( that melody, covered by everyone from The Doors to Bowie) and her six companions find a collective rhythm that makes Weill's returning variations feel like a genuine haunt rather than a device. Kenneth Kellogg's Trinity Moses brings scowling, low-register danger, and sparks magnificently against Mark Le Brocq's Fatty the Bookkeepers' all blazing tenor and New Jersey-accented chaos. Together they promise glamour and deliver grime, which is precisely the point. Andre de Ridder conducts his ENO debut with confidence, building the later acts toward sweeping choral crescendos that are almost consoling, until you remember what they're actually about.

The ENO Chorus themselves deserve a paragraph. Powerful, committed, making an unanswerable case for what a permanent ensemble can do — and doing so at a moment when their own future remains unresolved. In a city where the only unforgivable crime is having no money, the irony is not lost. They were the stars tonight.

One unavoidable complaint: for the final twenty minutes, unfiltered horizontal stage lights blazed directly into the side stalls -both sides, meant to backlight the full company on stage (?), they still burned through. Rows of the audience sat with eyes shut, heads aching, reduced to listening. The ENO must fix this before the remaining shows. What is otherwise a bold, queer-spirited and bracingly relevant evening deserves to be properly seen — all of it.

Mahagonny runs for two more performances. The ticket price is, as the opera itself might argue, the least of what you'll pay — but it is very much worth it.

18th & 20th February 2026, London Coliseum.

More info or to book via ENO website

Support independent LGBTQ+ journalism

Scene was founded in Brighton in 1993, at a time when news stories about Pride protests were considered radical. Since then, Scene has remained proudly independent, building a platform for queer voices. Every subscription helps us to report on the stories that matter to LGBTQ+ people across the UK and beyond.

Your support funds our journalists and contributes to Pride Community Foundation’s grant-making and policy work.

Subscribe today

Comments ()