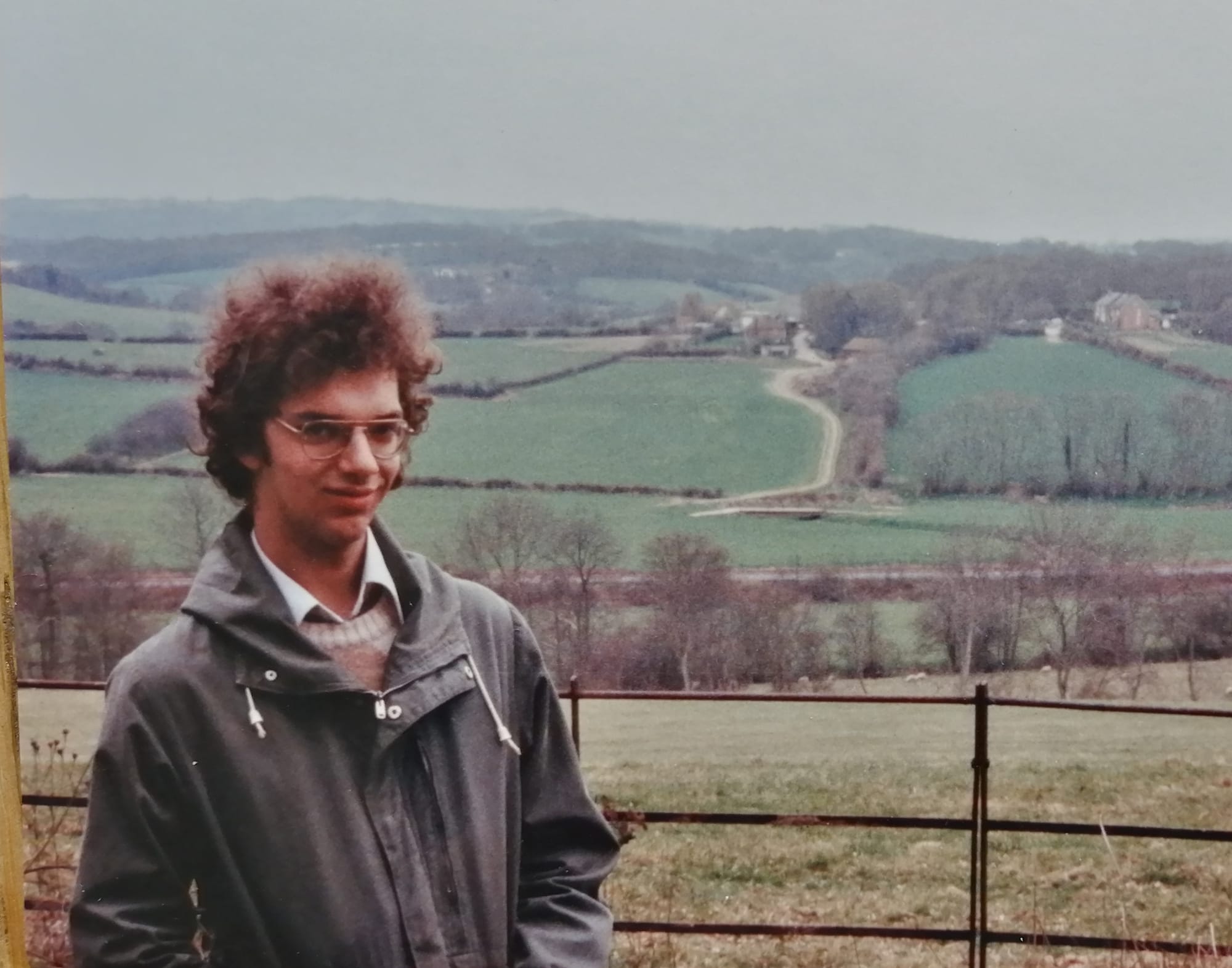

"We Never Expected to Be Here." Jim's story

When Jim was diagnosed with HIV in 1991 doctors told him he’d likely have two years. Today, he’s collecting his state pension. His story spans fear, anger, resilience, and activism, reminding us why World AIDS Day is both a memorial and a celebration.

When Jim was diagnosed with HIV in 1991 at the age of 31, doctors told him he’d likely have two years once AIDS developed. He never expected to see his 40th birthday - yet today, he’s collecting his state pension. His story spans fear, anger, resilience, and activism, reminding us why World AIDS Day is both a memorial and a celebration.

When you were first diagnosed, what did doctors tell you about your life expectancy?

I was diagnosed at 31 in early 1991. They told me I'd likely have two years once I developed AIDS, but this was ‘as long as a piece of string’, but likely five to 10 years.

I had PCP - an AIDS-defining infection - six years later and never expected to reach my 40th birthday. Against all expectations back then, and developing PCP (a serious fungal infection that is an AIDS-defining illness) six years later, I not only reached 40, but am now receiving my state pension.

You've lived through the darkest days of the epidemic. What was it like watching friends and lovers disappear while wondering if you'd be next?

Traumatic. It turned life expectations on their head, decimating my friendship circle. I hoped so hard that my elderly parents would die before me, before they might notice my ill health. I felt anger with those who chose to die - refusing to try the newly discovered combination therapies in '96, or choosing euthanasia in '97 in the Netherlands - both saying the new meds won't work, you'll be next.

When you look at photos from Pride marches or community events from the 80s and 90s, how many faces are still with us?

Just a very small number. HIV took many in the '80s and '90s. Other conditions, including old age, took others more recently.

There's often talk about "AIDS survivor syndrome." How do you carry the memory of those we lost?

When I started combination therapy in January '97, it wasn't known how long it would be effective—no previous meds had worked for more than a few months. So I never knew when I'd actually 'survived'. Life just went on, my health slowly but surely improved over the next few years. I returned to work, life went on and on. Coming further into the 21st century, I feel lucky to be one of the exceptional few who came through that period. I've been fortunate not to have felt the negative aspects of survivor syndrome, such as guilt.

What has surprised you most about growing older as an HIV long-term survivor?

Nothing has surprised me. I've had medication side effects for almost 30 years and I've learnt to live with them. Fortunately, I've never experienced a lack of understanding or any stigma within the healthcare system in this country - though I did experience homophobia and HIV stigma within the Dutch healthcare system, where I was from the mid-'90s to mid-'00s.

What do you want younger people living with HIV today to understand about the journey to get here?

The journey when it started was rough terrain. In the '70s and '80s, homophobia was endemic and ingrained into society - the local press, national press, politicians of all shapes and sizes. With this as a backdrop, HIV stigma and lack of compassion flourished. Key people like Princess Diana helped break the taboo and challenge the stigma. But we fought against the prejudice and built our own safe spaces, creating our own support systems like Body Positive Brighton and Open Door.

What do younger LGBTQ+ people need to know about what came before?

That our journey started with the queer community coming together to fight HIV, support those affected, and fight society for dignity and better care. Queer social life was as much based in community groups and organisations as in commercial spaces. Organisations like GLF, Sussex Uni Gay Soc, and CHE in the '70s set the scene of radicalism and anger at a society that rejected queer people. We created our own queer communities with not just political action but social activities - gay and lesbian discos, film seasons, social groups, discussion groups. Out of these roots, the HIV/AIDS community sprang into action in the 1980s.

What brings you joy and purpose now?

Building community. Giving to society. Working in and with the HIV community and also volunteering with my neighbourhood community in Seaford. Being with my family - both chosen family and blood relatives. Social life. Play. Music. Nature.

If you could send a message to your younger self who first received their diagnosis, what would you tell them?

The world will become a far better place.

Jim’s story is a testament to resilience and community. From the fear of the early '90s to the activism that shaped today’s treatments, his voice reminds us why World AIDS Day matters: to honour those we lost, celebrate those who survived, and keep fighting for dignity and care for all.

You can read the other interviews in this series here:

Support independent LGBTQ+ journalism

Scene was founded in Brighton in 1993, at a time when news stories about Pride protests were considered radical. Since then, Scene has remained proudly independent, building a platform for queer voices. Every subscription helps us to report on the stories that matter to LGBTQ+ people across the UK and beyond.

Your support funds our journalists and contributes to Pride Community Foundation’s grant-making and policy work.

Subscribe today

Comments ()