Thatcher's Centenary: No Pride in Her Legacy

For many in the LGBTQ+ community, the centenary of Margaret Thatcher’s birth is not a celebration but a stark reminder of a painful legacy - one shaped by exclusion, censorship, erasure and institutionalised homophobia.

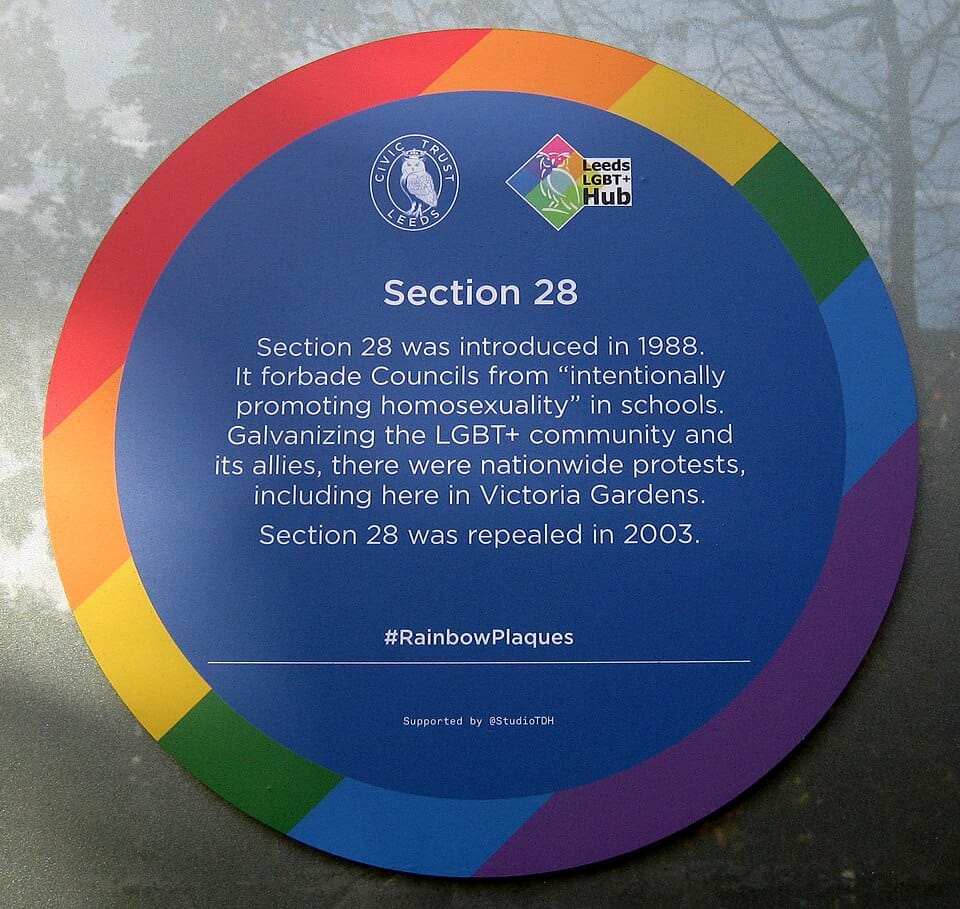

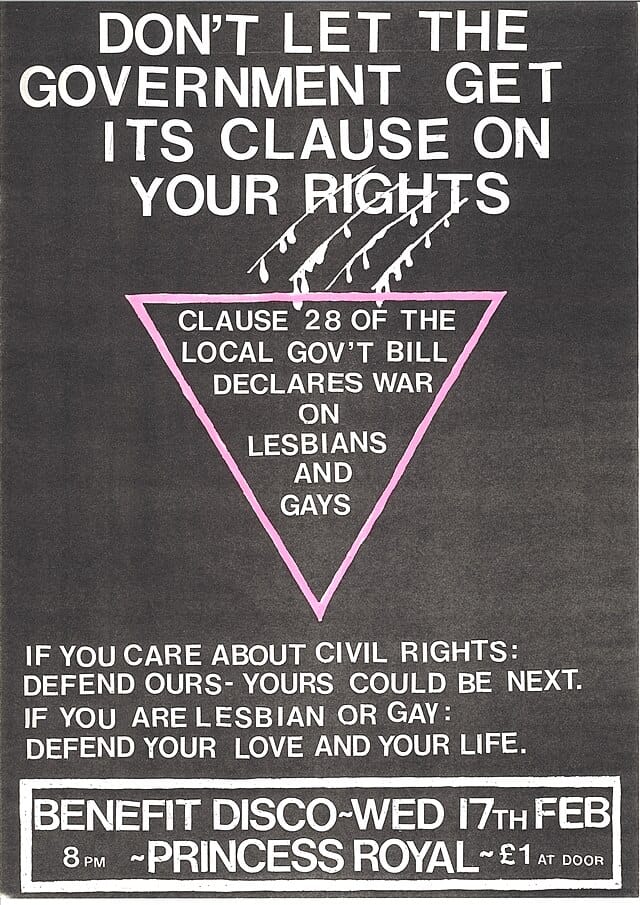

The government of Britain’s first female Prime Minister introduced one of the most damaging pieces of legislation in modern British LGBTQ+ history: Section 28 of the Local Government Act 1988. This clause prohibited local authorities from “promoting homosexuality” or teaching “the acceptability of homosexuality as a pretended family relationship” in schools.

Section 28 did not criminalise homosexuality, but its impact was profound. Teachers feared disciplinary action for even acknowledging LGBTQ+ identities. Libraries removed books with queer themes. Youth support groups were shuttered. The law created a climate of fear and silence, depriving a generation of LGBTQ+ youth of affirmation and safety in their formative years.

Catherine Lee, a former teacher who worked under Section 28, recalls the emotional toll: “I hid the fact that I lived with my girlfriend. I ignored homophobic bullying in corridors. I lived a half-life as a teacher, and I let down the young queer people in my schools”.

Thatcher’s anti-LGBTQ+ stance galvanised a wave of activism. In 1988, three lesbian protesters famously abseiled into the House of Lords. Others stormed the BBC newsroom, handcuffing themselves to cameras during a live broadcast. Actor Ian McKellen came out publicly in protest, helping to launch Stonewall, now one of Britain’s leading LGBTQ+ rights organisations.

These acts of defiance were not just symbolic — they were deeply British in their resolve and creativity. As historian Paul Baker notes, “The protests were bold, but often carried out with a uniquely British sangfroid - polite, witty, and determined”.

Though Section 28 was repealed in Scotland in 2000 and in England and Wales in 2003, its legacy lingers. Many LGBTQ+ adults who grew up under the law still carry the scars of silence and shame. The law’s chilling effect on education and public discourse has had long-term consequences for mental health, visibility, and inclusion.

Even today, some LGBTQ+ educators and students report echoes of Section 28 in the form of self-censorship and institutional hesitancy. As Britain reflects on Thatcher’s centenary, it must also reckon with the enduring damage of her policies.

As the HIV/AIDS epidemic began to devastate the UK’s LGBTQ+ community in the early 1980s, the Thatcher government’s response was marked by hesitation, moral panic, and a reluctance to confront the crisis head-on. While Health Secretary Norman Fowler pushed for a bold public health campaign - culminating in the infamous “Don’t Die of Ignorance” adverts and leaflets sent to every household - Thatcher herself was deeply uncomfortable with the campaign’s explicit messaging. She feared that references to “risky sex” and anal intercourse would corrupt young people, even suggesting that such information might do “immense harm” if read by teenagers.

Thatcher’s discomfort went beyond language. She vetoed a ministerial broadcast on HIV awareness, despite cross-party support, and reportedly told Fowler, “You mustn’t become known just as the minister for AIDS.”

As drag shows, poetry readings, and political panels mark Thatcher’s 100th birthday in Grantham, her hometown, LGBTQ+ Britons remember a different story - one of resistance, resilience, and the fight for dignity in the face of state-sanctioned erasure.

Comments ()