Gary's story: Living Through the Epidemic

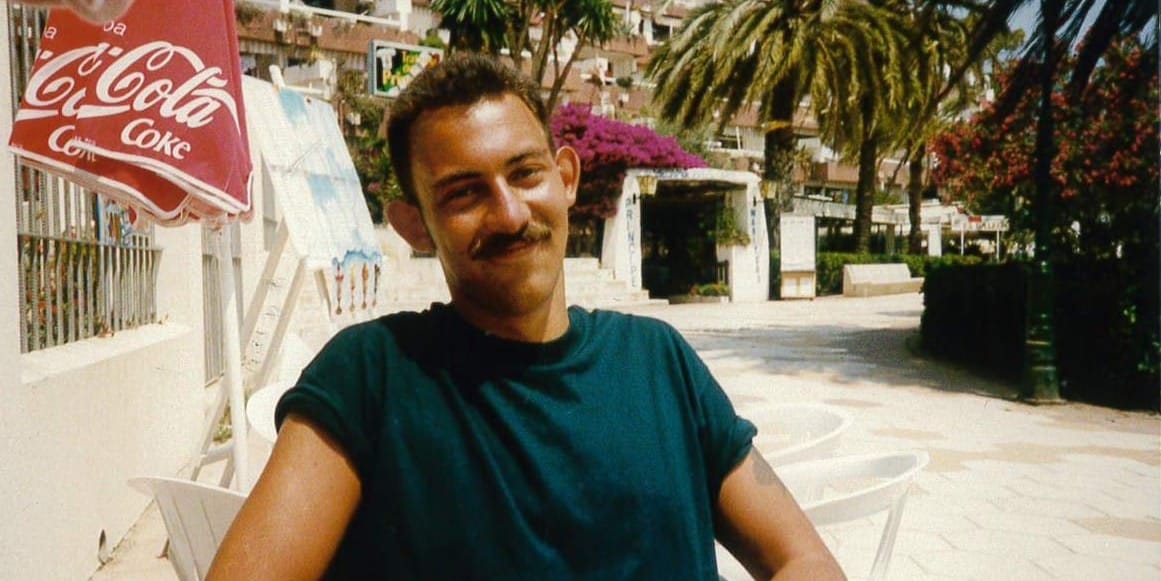

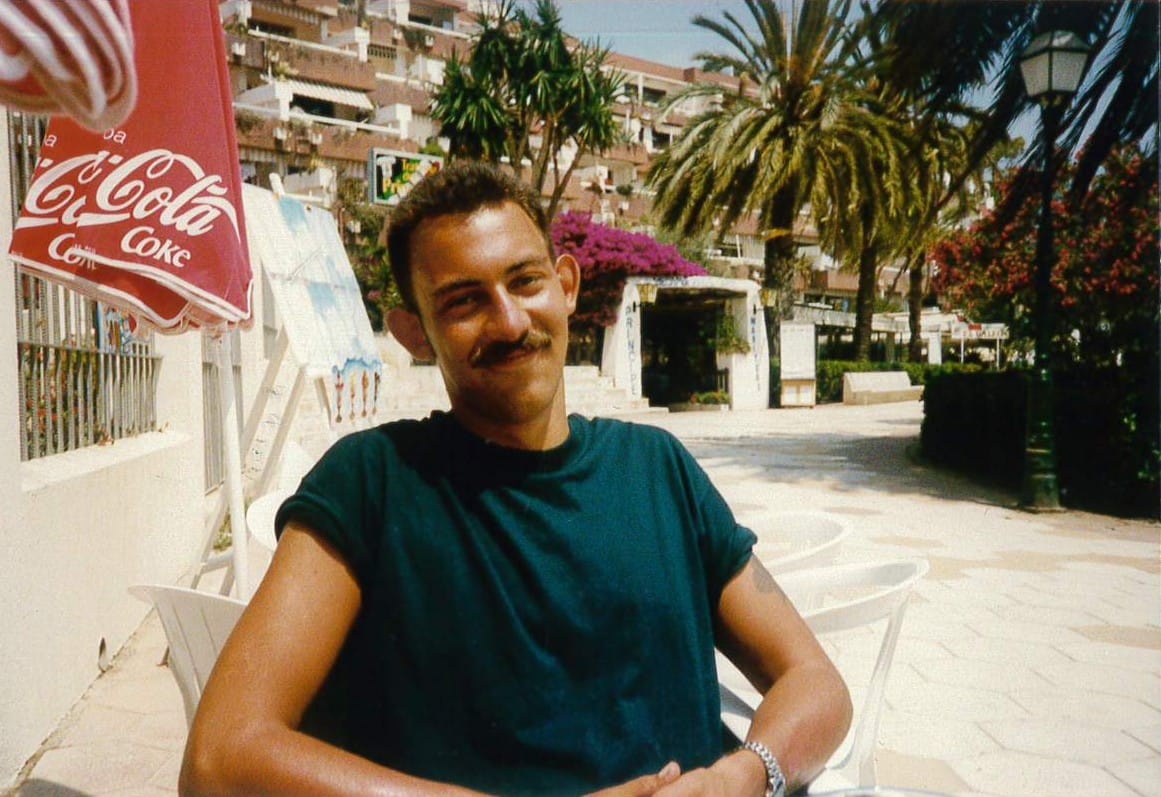

Gary offers a perspective many younger LGBTQ+ people have never heard - the voice of someone who wasn't supposed to survive. Diagnosed in 1992 in Brighton alongside his partner, now approaching sixty, he's older than the men he once looked up to, all of whom died in their thirties and forties.

Gary offers a perspective many younger LGBTQ+ people have never heard - the voice of someone who wasn't supposed to survive. Diagnosed in 1992 in Brighton alongside his partner, Gary has lived through the loss of four partners and every single friend from his close circle.

Now approaching sixty, he's older than the men he once looked up to, all of whom died in their thirties and forties. His story reminds us that behind the medical advances we celebrate today lies a generation-sized absence, and that living well with HIV means more than viral suppression - it means carrying forward the love and resilience of those who didn't make it.

When you were first diagnosed in 1992, what did doctors tell you about your life expectancy?

I was diagnosed at the same time as my partner, also called Gary. He was already showing distressing symptoms of AIDS dementia, severe weight loss, the 'obvious' signs of progression to AIDS. My own health hadn't deteriorated and I told the consultant I didn't want any discussion on my own life expectancy – all my focus needed to be on caring for Gary, who was so clearly ill. Walking home that day, I remember thinking 'at least now, I know'.

It felt eerily calm, perhaps some sort of shock, but I remember that strong feeling of knowing I could now do something with this knowledge. The clinic nurses spoke about doing everything possible to stay well, saying it could be "up to five years or more before I got ill" - they "just didn't know". The clinic did persuade me to take AZT and DDI, horrible medications and side effects, which I did for a while. But those conversations were happening while Gary's health was deteriorating rapidly. I needed to be strong for us both. I didn’t want to hear or contemplate anything that might detract from that.

You've lived through the darkest days of the epidemic. What was it like to watch friends and lovers disappear?

My whole adult life has been lived with the impact of HIV. I came out in my teens in the early 1980s, and HIV felt distant at first, but ever present as I navigated safer sex, often uncertain of what risk I'd encountered. I've been fortunate to have lived my whole life in Brighton - those deep roots and community familiarity have been helpful.

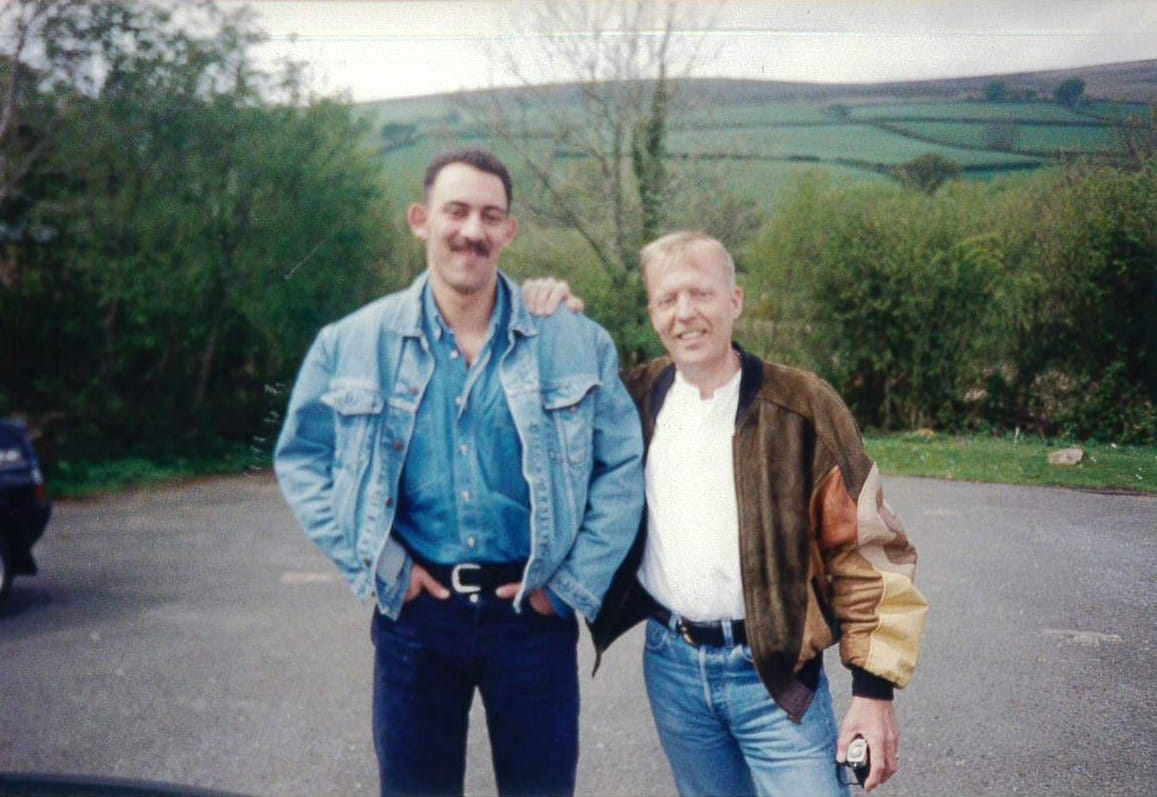

The reality of people getting ill and dying came closer, rapidly and hurtfully. Like so many younger gay men on the 'scene', we were part of a community with so many older guys - denim jeaned, booted, tight shirted, thickly moustached 'clones'! Looking back now, those 'older guys' were often only in their thirties, forties, fifties. It feels strange and upsetting to now be so much older than many of them, knowing those ages aren't actually 'old' at all.

However, the reality of people getting ill and dying came closer, rapidly and hurtfully. The HIV-related illnesses were all around us in their rawest, most debilitating and often dehumanising form. People would disappear from view, only to hear they'd died shortly after. It was ongoing, week after week, month after month. Whole friendship groups lost, funerals a constant. Four of my partners died - distressing AIDS dementia, cancers associated with HIV. It felt like the disappearance of almost a whole generation of gay men.

I never really wondered if I'd be next. My thoughts were usually on what best to do for those close to me. Everyone in my close friendship group was diagnosed HIV positive, but they were all immensely compassionate and deeply committed to caring for each other in every way. Perhaps as part of my own coping I was swept up in this tide of compassion - it felt empowering at a time that could otherwise be fear. I'll be forever grateful to those men who genuinely cared and fought for each other's rights. They are heroes to me.

This is the type of peer-support that I experienced and shared, and still value over all to this day; true, authentic human rather than professionalised peer-connection, life-changing support between people as part of caring friendship networks and brilliant community HIV organisations such as Open Door. The HIV-related illnesses were all around us to see in the rawest, most debilitating and often dehumanising form. It felt like the disappearance of almost a whole generation of gay men from our own lives, from the life and future of our gay community and culture.

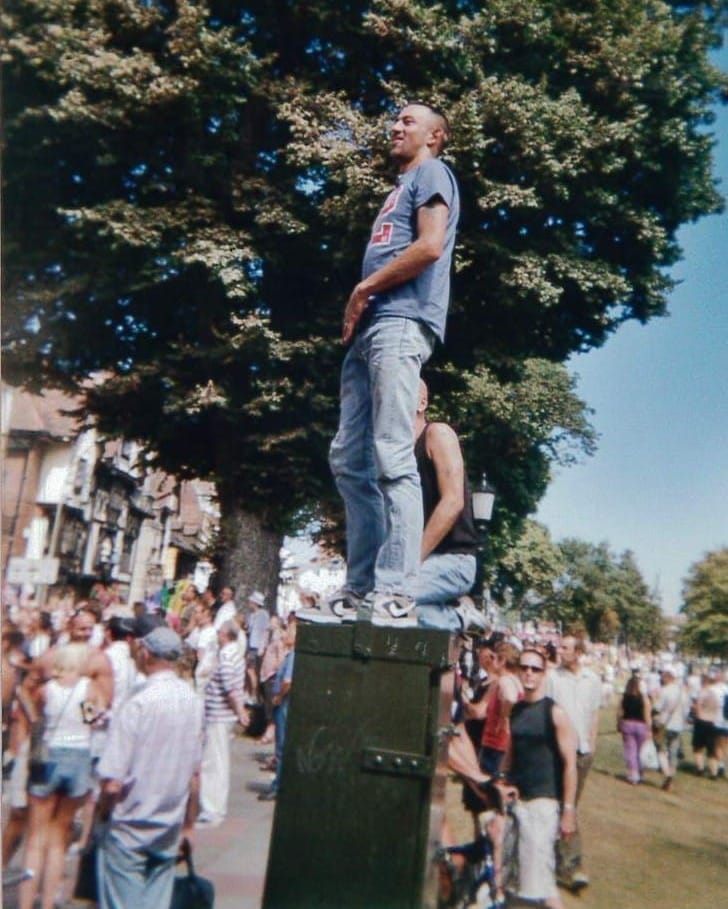

When you look at photos from Pride marches or community events from the '80s and '90s, how many faces are still with us?

Today I see none of the faces of people I know to have been diagnosed with HIV. They have all died, all so much younger than my own age now. That adds to the sadness and influences the adjustment to life with HIV in these times of greater hope. I think back to my partners, all who died in their thirties or forties when I was up to 16 years younger. I looked up to them as wise, more experienced men, which they were. But now, having journeyed through all those ages myself, I know they were not 'old' at all. They dealt with so much, so young. I honour them even more for that.

How do you carry the memory of those we lost?

I feel blessed to have known and loved so many wonderful people living with HIV and to have been in four close, loving, life-affirming relationships with Steve, Gary, Mike, and David. There has been anger, tears, loneliness, despair at losing them and the entire close friendship group I was part of. An occasional worry - did I do all I could? But these feelings are natural, and I forgive myself. I did my best in the circumstances.

Throughout, I've been able to call on and still feel the love I shared with my partners. I know they would want me to be happy - they all said as much - to enjoy life to the fullest, to survive where they did not. So strong was our love, I carry it with me, sometimes quietly and naturally as part of everyday life. At other times more intentionally, taking time to remember the joy of the love we shared and how we faced adversity together.

What has surprised you most about growing older as a long-term survivor?

The healthcare system has improved immensely. My experience is now one of understanding, respect and kindness. Things are nothing like they were in the early days. Despite occasional lack of knowledge or clumsy interactions that can be challenged and educated upon, I don't think we should catastrophise. Great work is going on around HIV awareness and ending stigma in healthcare.

The most surprising thing hasn't been negative experiences of healthcare, but the lack of general understanding of the social and emotional impact of having lived for so long with HIV. Simply being effectively on treatment is not the whole picture. I just wish people would understand that beyond the excellent treatment and clinical care available, there can still be emotional and social impact of living longer and older with HIV.

What do you want younger people living with HIV to understand?

Where younger people are feeling their HIV diagnosis a challenge, I'd hope to share insights that things can change for the better, feelings of despair and worry can subside and be overcome. Stay connected to people or things that share or enable these outlooks. Talking openly as part of trusted and supportive relationships can be transformative.

I'd hope to share the personal empathy that develops through decades of complex life experiences, personal reflection, and also that which was passed on to me by others who were older before they died. There are multiple generational legacies of hope and resilience.

What do younger LGBTQ+ people need to know about what came before?

I hope younger LGBTQ+ people will seek out and hear the history of loss and struggle, and importantly the stories of strength of people and communities living with HIV. There are examples of vulnerability, compassion, bravery, community cohesion and impact that are entirely relevant to today's challenges and inequalities.

Know that we have lost so very many people from earlier generations. Had HIV not emerged, our numbers would be larger by the millions. Just imagine how much greater our already considerable achievements and visibility would have been as a community. Don't confine these experiences to history - know and use them to shape our improved future.

What brings you joy and purpose now?

I love working with others in community-based support and activities. Joy and purpose is being with and alongside people; fulfilment is seeing others happy and well. As I approach my sixties, I look forward enthusiastically to this next stage of life. I look forward with intention to the growing fulfilment of the years ahead, knowing so many I loved are not here to experience this.

That includes a little less unnecessary 'noise' in life, being close with people with shared values and those who live with authenticity and kindness, enjoyment of life with my partner, being outdoors and with nature.

If you could send a message to your younger self, what would you say?

Things can change, and if difficult now, won't always feel this way. Exceptional and completely unimaginable good things can happen. Be kind and forgiving to yourself and others, know you are loved and can love, share and talk, and life can become easier.

Today, here in the UK, we are living with HIV in a way that was unimaginable just decades ago. That is something to value and celebrate and to draw strength from.

Gary's journey from the terror of the early AIDS years to the relative stability of modern treatment is a testament to both medical progress and human resilience. But as he makes clear, survival comes with its own complexities. On this World AIDS Day, his message is simple: remember what was lost, honour those who cared for each other through the darkest times, and ensure younger generations understand that the freedoms they inherit were paid for with millions of lives. The epidemic may have changed, but for long-term survivors, it will never truly be over.

You can read the other interviews in this series here:

Support independent LGBTQ+ journalism

Scene was founded in Brighton in 1993, at a time when news stories about Pride protests were considered radical. Since then, Scene has remained proudly independent, building a platform for queer voices. Every subscription helps us to report on the stories that matter to LGBTQ+ people across the UK and beyond.

Your support funds our journalists and contributes to Pride Community Foundation’s grant-making and policy work.

Subscribe today

Comments ()